“Doctor, I have an upset stomach” -- What is “dyspepsia”?

“Doctor, I have pain in the abdomen” -- What is NOT “dyspepsia”?

How common is dyspepsia?

“So I have dyspepsia. What is causing it?”

Two important factors to consider in diseases associated with dyspepsia

Approach to the patient with “uninvestigated dyspepsia”

What about an abdominal ultrasound?

If a cause for dyspepsia is found, what are the treatments?

What is functional dyspepsia?

Dyspepsia and normal endoscopy: Two notes of cautionThe term “dyspepsia”

is used in medical writing, but it is not used in everyday life, and patients

do not come to a doctor saying “I have dyspepsia.” However, it is very common

for people to express that they have “upset stomach,” “indigestion,” “acid

stomach,” “acid indigestion,” “stomach pain,” “stomach burning,” or “stomach

fullness.” These and similar terms reflect the experience of abdominal pain or

discomfort, often worsened by eating. It is also common for people to complain

of “heartburn,” which to some means upper abdominal burning alone, but for many

it consists of a burning sensation in the chest.

A concise definition of dyspepsia is

chronic or recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort in the upper abdomen.[1]

Researchers debate the distinction between “pain” and “discomfort” but most

recognize that some patients with “dyspepsia” do not have pain, yet they are

bothered by other symptoms that can include an uncomfortable sensation in the

upper abdomen, losing appetite after eating very little, and feeling full after

eating.[2] Some patients may also experience nausea, an unpleasant sensation

that they may soon need to vomit. The term “dyspepsia” is used to capture this

group of digestive symptoms, which are believed to arise from the stomach and

upper gut.[3]

It has been controversial whether “heartburn” should be considered separately

from “dyspepsia” or whether it should be part of the “dyspepsia umbrella.” The

practical reason for a distinction is that “heartburn” is more likely than

“dyspepsia” to be explained by acid reflux (passage of stomach acid to the

esophagus, which is the “swallowing tube” in the chest, between the mouth and

stomach). The approach to patients with acid reflux, or gastroesophageal reflux

disease (GERD), differs from the approach to patients with dyspepsia without

prominent “heartburn.” For this reason, recent guidelines recommend that

patients who have heartburn predominantly should be considered initially to

have gastroesophageal reflux disease and should not be grouped with patients

with dyspepsia.[2-4] However, it is recognized that some patients with

“dyspepsia” do actually have gastroesophageal reflux disease without classic

heartburn, and that some without demonstrable gastroesophageal reflux disease

may experience heartburn as one of their symptoms.

“Doctor, I have pain in the abdomen” -- What is NOT “dyspepsia”?

Patients with the variety of symptoms

described above may be said to have “dyspepsia,” but it is important to

recognize patients with other patterns of symptoms that should not be confused

with “dyspepsia.” Acute abdominal pain (pain that comes on suddenly and has not

happened before) is not dyspepsia. Depending on the nature of the pain and

other symptoms, acute abdominal pain may represent medical emergencies such as

serious inflammation of the gallbladder or pancreas, intestinal blockage, loss

of blood flow to the intestines, appendicitis, a gynecological emergency, a

heart attack, or other serious diseases. Severe acute abdominal pain should be

considered an emergency.

Gallstones can lead to recurrent attacks of upper abdominal pain, which may be

severe and may be accompanied by nausea, back or shoulder pain, and sweating.

People may often feel completely fine for weeks between such attacks. This

symptom pattern should be distinguished from the pattern of more frequent –

even daily – and generally milder symptoms that is implied by

“dyspepsia.”

It is common for patients to experience

abdominal pain and changes in their bowel function, such as diarrhea or

constipation. These symptoms may have many causes, including an acute

infection, metabolic problems, inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, and

irritable bowel syndrome. This group of persons should be considered separately

from those with dyspepsia.

How common is dyspepsia?

In Western countries, approximately 25% of

people experience dyspepsia in any given year.[1] Many do not see a doctor, and

self-medication is common, as attested to by the many products that are

available over the counter for various digestive symptoms. For most persons

with dyspepsia, it is a chronic problem, although the intensity and frequency

can vary over the years. Approximately 1% of people may develop new dyspepsia

every year, with a similar number becoming free of dyspepsia, so that the

number of people with dyspepsia in the population remains stable.[1] Dyspepsia

is a common reason for a medical visit, accounting for 2-5% of family practice

consultations and a significant number of referrals to gastroenterologists.

“So I have dyspepsia. What is causing it?”

Before discussing how to approach patients

with dyspepsia, including what tests or treatments should be considered, it is

important to understand the possible causes of dyspepsia and how likely they

are. Appreciating these possible causes lays the logical foundation for the

currently recommended approaches to patients with dyspepsia.

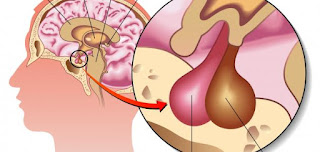

In patients who have endoscopy (a “camera scope” exam of the upper esophagus,

stomach, and upper small intestine, known as the duodenum) to try to determine

the cause of dyspepsia, the types of abnormalities that can be uncovered

include:

- Stomach or

duodenal ulcer

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease with or without visible damage to

the esophagus (esophagitis)

- Stomach cancer, which is the least common underlying disease in

persons with dyspepsia, but fear of which may drive people to see a doctor

- No

abnormality

Patients may find it remarkable, but over half of people with dyspepsia do not

have any identifiable abnormalities on routine medical testing. This group of

people is labeled as having “functional dyspepsia,” also known as “non-ulcer

dyspepsia” or “idiopathic dyspepsia” (“idiopathic” means we do not know what

causes it). Not finding an abnormality can be a source of both relief and

frustration for patients and doctors, and the management of persons with

functional dyspepsia can be challenging, as discussed below.

The likelihood of the various cause of dyspepsia differs between countries and

even between specific locations within countries, and is affected by patient

age and other factors. In North America, it is estimated that peptic ulcer

disease accounts for 5-15% of cases of dyspepsia, gastroesophageal reflux

disease for 15-30%, cancer for less than 1-2%, and functional dyspepsia for

over 50%.[1] Older patients are more likely to have cancer than younger

patients, but even in older patients cancer is an uncommon explanation for

dyspepsia.

Two important factors to consider in diseases associated with dyspepsia

There are two very important factors to

consider when developing management strategies for persons with dyspepsia.

These are aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as

ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil) and naproxen (Aleve), and the bacterium Helicobacter

pylori (H. pylori). Both are related in important ways to dyspepsia and its

associated diseases.

Aspirin and NSAIDs may cause dyspepsia without causing ulcers. They may also

cause gastrointestinal damage ranging from minor erosions (small areas of

injury that are too small and superficial to be called an ulcer) to severe

ulceration. Ulcers, in turn, may or may not cause dyspepsia. Serious

complications of ulcers can include bleeding, bowel blockage or perforation,

and sometimes patients do not have dyspepsia before these complications occur.

These relationships between aspirin and NSAIDs and dyspepsia and its associated

diseases highlight why it is important to establish whether dyspeptic patients

are using aspirin and NSAIDs. This includes patients who have not yet had any

testing, “investigated patients” (those who have had endoscopy) with proven

ulcer disease, and also in those with no abnormality on upper endoscopy.

H. pylori is a bacterium that lives in the stomachs of hundreds of

millions of people around the world.[5] It is more common in developing

countries and in Asia, Africa and South America than in Western countries.

There is a clear and strong association between H. pylori and

peptic ulcer disease, H. pylori and stomach cancer, and H.

pylori may also be important in a small proportion of persons with

functional dyspepsia. In persons with ulcer disease due to H. pylori,

cure of the infection almost eliminates the chance of developing an ulcer

again, whereas failure to eradicate H. pylori is associated

with a very high rate of recurrent peptic ulcer disease.[6] The vast majority

of people with H. pylori do not develop ulcer disease or

cancer, but H. pylori causes inflammation and other changes in

the stomach lining that can eventually lead to stomach cancer in a small

fraction of infected persons. These relationships between H.

pylori and dyspepsia and its associated diseases form the basis for

the current recommendations on how to approach persons with dyspepsia.

Approach to the patient with “uninvestigated dyspepsia”

A person with dyspepsia who has not had

medical testing (usually endoscopy) to try to determine a cause has

“uninvestigated dyspepsia.” Many studies have tried to determine the optimal

approach in these patients. Unfortunately, the clinical story alone does not

allow doctors to make an accurate diagnosis without testing. Current recommendations

on how to approach patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia are based on an

appreciation of how common the different possible underlying diseases are, and

on the available research studies.[1-3, 7, 8] Performing endoscopy up-front on

all patients with dyspepsia would be the most direct route to determining a

specific diagnosis, but this is not practical in the primary care setting, and

it is not likely to be a viable strategy because it is too costly.

A reasonable stepwise approach begins with determining if a person complaining

of dyspeptic symptoms is taking aspirin or NSAIDs. If so, and if these

medications can be stopped readily, it is reasonable to stop them and observe

to see if the dyspeptic symptoms go away. If the person has a strong reason to

take low-dose aspirin, such as prevention of heart attack or stroke, or to take

NSAIDs, such as treatment of arthritis pain that does not respond to

acetaminophen (Tylenol), a reasonable approach is to take a proton pump

inhibitor along with the aspirin or NSAID. Proton pump inhibitors are

medications that decrease the amount of acid produced by the stomach, and these

medications can improve the dyspepsia associated with aspirin or NSAIDs, as

well as heal or prevent ulcers. The available proton pump inhibitors include

omeprazole (Prilosec, now also available in the United States without

prescription as Prilosec OTC), lansoprazole (Prevacid), rabeprazole (AcipHex),

pantoprazole (Protonix) and esomeprazole (Nexium). It is advisable to take the

lowest possible dose of aspirin and NSAIDs and to use these for the shortest

possible time.

Older persons have a higher risk of cancer than younger persons, and for this

reason guidelines recommend that older persons presenting with dyspepsia should

undergo prompt endoscopy. The precise age cut-off is debated and depends on how

likely cancer is in a given region and on the availability of health services,

but prompt endoscopy is sensible in persons older than 45-55 years of age

presenting with dyspepsia.[1-3]

Most persons with cancer of the upper digestive system have “alarm symptoms”

such as difficulty swallowing, nausea and vomiting, weight loss, vomiting

blood, or black stools (reflecting internal bleeding). Unfortunately, the

presence of alarm symptoms does not seem to be very useful in identifying

persons with cancer versus those without cancer.[9] Nonetheless, most experts

agree that patients with dyspepsia and alarm symptoms should undergo prompt

endoscopy.[2-4]

In younger persons (under 45-55 years of age) without alarm symptoms, the H.

pylori “test-and-treat” strategy is recommended.[2-5, 8] These persons

are unlikely to have cancer, a minority may have peptic ulcer disease or

gastroesophageal reflux disease, and most would have a normal upper endoscopy.

In the absence of aspirin or NSAID use, peptic ulcer disease would likely be

due to H. pylori. Treatment of H. pylori can

have several benefits:

- It treats peptic ulcer disease and nearly eliminates the risk of

recurrent ulcer.[6]

- When H. pylori was first discovered, it was hoped

that treating it might cure most persons with dyspepsia but without an

ulcer. Unfortunately, this is not the case, but a small minority of these

patients does seem to benefit. It is estimated that 10-25 persons with

functional dyspepsia and H. pylori need to be treated in

order to cure one.[10]

- It has the potential to decrease the risk of developing ulcers or

stomach cancer later in life.

The currently recommended tests for H. pylori are a stool test

(stool antigen test) or a breath test (urea breath test). If a test for H.

pylori is positive, the recommended first-line treatment is triple

therapy with a proton pump inhibitor combined with amoxicillin 1 gram, and

clarithromycin 500 mg or metronidazole 500 mg, all taken twice a day for 10-14

days.[5] It is important to complete the entire treatment course as prescribed

in order to increase the likelihood that H. pylori will be

eradicated.

If H. pylori is very rare in a particular region, it may be

most cost-effective to offer young persons with dyspepsia without alarm

symptoms a trial of proton pump inhibitor treatment once a day for 4-8 weeks

and then reassess. However, eradicating H. pylori could

decrease future ulcer and cancer risk, and this opportunity is lost when a

proton pump inhibitor trial is given instead of testing for H. pylori.

In Western countries, most patients with dyspepsia will test negative for H.

pylori, leaving the question of how to manage this majority of patients. A

trial of proton pump inhibitor treatment once a day for 4-8 weeks is

recommended for several reasons:

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease is reasonably likely, and proton

pump inhibitors are excellent treatment for this condition.

- Symptoms in functional dyspepsia may improve with proton pump inhibitor

treatment.[11]

- Although ulcers are rare in the absence of H. pylori,

aspirin, or NSAIDs, most ulcers heal with proton pump inhibitor treatment.

Regardless of what initial approach is followed, a substantial number of

persons with dyspepsia will not feel better with the initial treatment or will

experience a return of their symptoms. The options at this point are to re-test

those who had eradication therapy for H. pylori and treat

again with a different regimen if infection persists, to switch from H.

pylori “test-and-treat” to proton pump inhibitor therapy or vice

versa, or to move on to endoscopy. Ultimately, it is reasonable to perform

endoscopy in persons who fail to improve after two attempts at therapy.

Although it is unlikely that endoscopy will uncover any serious abnormality at

this point, it is important to exclude cancer and it is possible that the

reassurance from a normal endoscopy may help decrease the anxiety over possible

serious disease. At the time of endoscopy, stomach biopsy should be performed,

and H. pylori should be treated if it is found on biopsy.

What about an abdominal ultrasound?

Abdominal ultrasound is unlikely to be

useful in patients with dyspepsia. As discussed above, it is important to

distinguish patients who may have pain from gallstones from those with

dyspepsia. Most people with gallstones do not have symptoms from them, and do

not need to have their gallbladder removed. The problem with looking for

gallstones in people with dyspepsia is that they may have gallstones by chance

alone. Removal of the gallbladder in these patients will not help and carries a

small but real risk of complications.

If a cause for dyspepsia is found, what are the treatments?

If endoscopy identifies an explanation for

dyspepsia, then directed management will be possible. Stomach cancer can be

treated depending on the type and extent. Gastroesophageal reflux disease can

be treated with acid suppression. The most potent acid-suppressing medications

are the proton pump inhibitors. Some patients with gastroesophageal reflux

disease may do well with the less potent histamine receptor antagonists such as

cimetidine (Tagamet), ranitidine (Zantac), nizatidine (Axid), or famotidine

(Pepcid), but proton pump inhibitors are usually needed in those with

esophagitis. Gastroesophageal reflux disease often requires long-term, ongoing

treatment. Peptic ulcer disease can be managed by eradicating H.

pylori and avoiding aspirin and NSAIDs. If aspirin or NSAIDs must be

continued, treatment with a proton pump inhibitor will decrease but not

eliminate the risk of ulcer recurrence.

The majority of patients with dyspepsia do

not have an identifiable abnormality at endoscopy, and they are diagnosed with

functional dyspepsia. Functional dyspepsia is one of the common “functional

gastrointestinal disorders,” which are conditions in which patients have

symptoms but standard medical testing is normal.[3] Beginning in the 1980’s,

leading researchers in the field of functional gastrointestinal disorders have

engaged in the “Rome process” (named after the city where the major meetings

for this group have taken place), which addresses multiple issues related to

the study of the functional gastrointestinal disorders. A major task of the Rome

process is to define symptom-based diagnostic criteria for these

disorders.

The Rome III pragmatic definition of functional dyspepsia, proposed in 2006, is

“the presence of symptoms thought to originate in the gastroduodenal region, in

the absence of any organic, systemic, or metabolic disease that is likely to

explain the symptoms.”[3] The Rome III diagnostic criteria for functional

dyspepsia are:[3]

1. One or more of:

a. Bothersome

postprandial (after eating) fullness

b. Early satiation

(early loss of appetite during a meal)

c. Epigastric

(mid-upper abdominal) pain

d. Epigastric burning

AND

2. No evidence of structural disease (including at upper endoscopy) that is

likely to explain the symptoms

* Criteria fulfilled for the last three months with symptom onset at least six

months before diagnosis

The Rome working group has proposed two distinct syndromes under functional

dyspepsia based on the belief that patients described by the two syndromes may

have different underlying abnormalities. These are the “Epigastric Pain

Syndrome,” which is characterized by pain or burning in the upper abdomen, and

the “Postprandial Distress Syndrome,” which is characterized by bothersome

fullness after a meal and/or early loss of appetite that prevents finishing a

regular meal.

Dyspepsia and normal endoscopy: Two notes of caution

Although most patients with dyspepsia and

normal endoscopy are categorized appropriately as having functional dyspepsia,

two notes of caution are needed. First, it is possible for patients to have

gastroesophageal reflux without visible esophagitis, and those with typical

heartburn and regurgitation (passage of stomach contents to the mouth) should

be considered to have gastroesophageal reflux disease and should be treated

with acid suppression. Second, many patients are treated with proton pump

inhibitors before endoscopy, and a small number of them may have had

esophagitis or ulcers when they were initially treated. With treatment,

esophagitis and ulcers can heal and endoscopy can then be normal. If an ulcer

was the cause of pain and the ulcer has healed, one would expect the pain to go

away. If the pain persists, that patient may have ulcer disease as well as

functional dyspepsia.

What causes functional dyspepsia?

Functional dyspepsia is an umbrella term

for what are likely to be a group of different underlying abnormalities. By

definition, standard medical tests do not show abnormalities in functional

dyspepsia, but multiple studies have shown that subgroups of patients with

functional dyspepsia exhibit differences from persons without functional

dyspepsia when specialized tests or research studies are performed.[1, 12]

These include abnormally slow emptying of food from the stomach and other

abnormalities in the motor function of the stomach such as inadequate

relaxation to accept a meal or weak contractions. Subgroups of patients with

functional dyspepsia display “hypersensitivity” to a variety of challenges

including distension of the stomach with a balloon, acid infusion into the

duodenum, or delivery of fat into the intestine. The link between these

abnormalities and patients’ symptoms is not clearly established.

It has been disappointing that in most persons with functional dyspepsia

and H. pylori infection, treatment of the infection does not

cure the dyspepsia. However, there is evidence that a small minority of these

persons do experience cure of their symptoms when H. pylori is

eradicated.[10] There is an association between functional dyspepsia and

psychological factors, including anxiety.

Can all persons with functional dyspepsia really be lumped together in one

group? If they don’t all have the same symptoms, do they all have one

“disorder”? Are there different causes for symptoms in different patients? A

major challenge has been that specific symptoms and specific physiological

“abnormalities” do not go hand in hand. Past attempts to divide people into

those with “ulcer-like” symptoms such as burning pain and those with symptoms

of “dysmotility” (abnormal muscle function of the gastrointestinal tract) such

as fullness or early loss of appetite have not been very successful because of

the significant overlap between groups. It remains to be seen whether the

“Epigastric Pain Syndrome” and “Postprandial Distress Syndrome” will prove to

be useful categories.

Sub-categorization of patients would be most useful if symptoms and/or specific

tests could identify groups that should receive different treatments.

Unfortunately, few treatments are available currently and most tests are

imperfect or impractical.

How is functional dyspepsia managed?

It is disappointing, but the reality is

that the treatment options for functional dyspepsia are limited. Some patients

may do well with education and reassurance. Even though symptoms tend to be

chronic, allaying the fear over serious disease may allow some patients to

adjust and live with their symptoms. No specific dietary advice is universally

successful, and patients should be encouraged to eat a normal, healthy diet.

Limiting fat intake may help some patients.

Many patients wish to try medications to decrease their symptoms and improve

their quality of life. Acid suppression with proton pump inhibitors or

histamine receptor antagonists may help some patients.[11] This may be due to

the fact that some patients who are labeled as having functional dyspepsia

actually have reflux, and that some others may have hypersensitivity to acid in

the stomach or duodenum. Antacids do not seem to be effective.[11] Medications

to improve the motor function of the stomach are limited, some are no longer

available, and it is not clear that available drugs help in functional

dyspepsia.[11]

Patients who have H. pylori should have treatment to eradicate

the infection.[5] It is estimated that 10-25 persons need to be treated to

achieve one cure in functional dyspepsia.[10] Given that there are few

treatment options for functional dyspepsia, these are actually reasonable odds

of success. Eradicating H. pylori may have the additional

benefit of decreasing subsequent risk of ulcer disease and cancer.

Antidepressant medications may help in functional dyspepsia even when patients

are not depressed, but there has been relatively little research in this area.[1]

These medications may affect the perception of symptoms. There is stronger

evidence that antidepressants help in irritable bowel syndrome, another classic

functional gastrointestinal disorder. Antidepressants are used in functional

dyspepsia in part based on an extension of the evidence in irritable bowel

syndrome. The tricyclic antidepressants include amitriptyline (Elavil),

nortriptyline (Pamelor), imipramine (Tofranil), and desipramine (Norpramin),

and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) include fluoxetine

(Prozac), sertraline (Zoloft), paroxetine (Paxil), citalopram (Celexa) and

fluvoxamine (Luvox). The rationale for using these medicines should be

explained to the patient since the doctor-patient relationship can be damaged

if patients look up information on the prescribed drug, learn it is an

“antidepressant” and question their doctor’s justification for prescribing the

medication.

There is some evidence that functional dyspepsia may improve with a variety of

psychiatric treatments.[13] These include hypnotherapy, cognitive therapy,

relaxation, and psychodynamic-interpersonal therapy. It’s not clear how

long-lasting the benefit may be, and these therapies are not currently

available for most patients.

Dyspepsia is very common. Patients with dyspepsia may be concerned that there is something “seriously wrong inside.” Fortunately, serious disease, including cancer, is a very uncommon explanation for dyspepsia. Older patients and those with “alarm symptoms” should have prompt endoscopy. Younger patients without alarm symptoms can be managed without endoscopy initially, with endoscopy reserved for those with persistent symptoms. Eradication of H. pylori infection treats peptic ulcer disease, can decrease the risk of cancer, and may help a minority of patients with functional dyspepsia. Acid suppression is excellent therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease and may help in functional dyspepsia. Although it can be challenging to treat functional dyspepsia, patients should be reassured that they are not at higher risk of cancer or other serious disease and that they have a normal life expectancy. A variety of treatments can be tried, and the focus should be on leading a normal life even if symptoms cannot be eliminated.

References

1. Talley

NJ, Vakil NB, Moayyedi P. American gastroenterological association technical

review on the evaluation of dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 2005;129:1756-80.

2. Talley

NJ, Vakil N. Guidelines for the management of dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol

2005;100:2324-37.

3. Tack

J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, Holtmann G, Hu P, Malagelada JR, Stanghellini V.

Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology 2006;130:1466-79.

4. Talley

NJ. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement:

evaluation of dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 2005;129:1753-5.

5. Malfertheiner

P, Megraud F, O'Morain C, Bazzoli F, El-Omar E, Graham D, Hunt R, Rokkas T,

Vakil N, Kuipers EJ. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori

infection: the Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut 2007;56:772-81.

6. Ford

AC, Delaney BC, Forman D, Moayyedi P. Eradication therapy for peptic ulcer

disease in Helicobacter pylori positive patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2006:CD003840.

7. Delaney

B, Ford AC, Forman D, Moayyedi P, Qume M. Initial management strategies for

dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005:CD001961.

8. Ford

AC, Qume M, Moayyedi P, Arents NL, Lassen AT, Logan RF, McColl KE, Myres P,

Delaney BC. Helicobacter pylori "test and treat" or endoscopy for

managing dyspepsia: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Gastroenterology

2005;128:1838-44.

9. Vakil

N, Moayyedi P, Fennerty MB, Talley NJ. Limited value of alarm features in the

diagnosis of upper gastrointestinal malignancy: systematic review and

meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2006;131:390-401; quiz 659-60.

10. Moayyedi

P, Soo S, Deeks J, Delaney B, Harris A, Innes M, Oakes R, Wilson S, Roalfe A,

Bennett C, Forman D. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori for non-ulcer

dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006:CD002096.

11. Moayyedi

P, Soo S, Deeks J, Delaney B, Innes M, Forman D. Pharmacological interventions

for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006:CD001960.

12. Tack

J, Bisschops R, Sarnelli G. Pathophysiology and treatment of functional

dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 2004;127:1239-55.

13. Soo

S, Moayyedi P, Deeks J, Delaney B, Lewis M, Forman D. Psychological

interventions for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2005:CD002301.